This year’s Connected Academics proseminar, now well into its second semester, has already provided so many valuable kinds of practical professional support for its participants, including me: exercises in job-advertisement analyses, skills translation, LinkedIn profiles, and networking, as well as activities like site visits, informational interviews, and panel discussions. But our regular meetings also provide important opportunities for emotional support, as many of us work through the highs, lows, and apathetic in-betweens of our graduate school careers. Occasionally we’ve dedicated time to sharing our mixed feelings about our experiences in school and on the job market, but more often than not our “therapy sessions” emerge organically as we discuss the more practical elements of transitioning from academia to other sectors.

For the most part—understandably—these therapeutic discussions have been a bit negative, as we’ve shared feelings of disappointment, shame, frustration, anger, and disbelief. Certainly, we face a lot of pressing concerns: our doctoral programs’ persistent lack of adaptability, our universities’ increasing reliance on adjunct faculty members, and the nationwide devaluation of the humanities. And we are some of the best candidates to propose solutions and enact change. But I worry that focusing too much on all the ways that we’ve been wronged will prolong our paralysis, increase our anxieties, and ultimately prevent us from getting great jobs. This is not just a concern for our cohort. So many of the discussions I’ve seen and heard in the academic community lately have been grounded in this elegiac impulse: “The Death of the University,” “As I Regard My Dying Career Prospects,” “To a Life Wasted in Dissertating” (all fictional titles, as far as I know, but you get the idea). We’re fixated on everything we have lost or are losing, letting ourselves become mired in gloom and doom.

So I’m putting on my Pollyanna hat (wide-brimmed straw with just the nicest blue silk bow!): consider this an official call for a shift to optimism. Bring back the ode, and let’s spend some time celebrating the positive qualities of graduate school rather than sounding its death knell. Isn’t this the point of the Connected Academics initiative anyway? Let’s focus on the tools we’ve acquired—including the connections we’ve made and the preparation we’ve had—and start recasting them for our coming careers, whatever they may be. Not that we should completely stop expressing our frustrations: communal complaining is, I think, an important step toward healing and organizing. But now that we’re building our professional identities as humanists-at-large, engaging with communities in academia and (especially) beyond, it’s crucial for us to think how prepared we are for this next step.

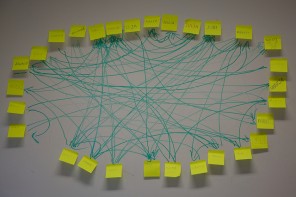

That means thinking about how our graduate experiences helped us: the ways in which we developed as scholars, teachers, professionals, and people. The crux of this push toward the positive is the art of translation—something we’ve been discussing in a variety of ways already. In our job-advertisement analyses, I felt such a sense of relief—as well as excitement about the possibilities opening up in front of me—as we talked about how our academic talents have a wide range of applications in different careers. This optimistic impulse, conveyed through skills translation, was also highlighted by several of the PhD-holding panelists in our meetings at the New York Public Library and the CUNY Graduate Center.

Valuing our graduate careers is strategic; we want to be able to show potential employers a narrative of consistent development, of moving upward and forward. This doesn’t mean we weren’t chaotic, confused, or misdirected at times—we just never stopped accumulating valuable experiences and knowledge. And beyond the job market, this optimism is important personally: without it, how soul-crushing to imagine that all our years of hard work might be pointless, irrelevant, and undervalued by nonacademic employers. Instead, let’s think about those years as a legitimate period of learning and employment, a foundation for the many options that are opening up to us now.

Catherine Burton is a doctoral candidate in English at Lehigh University, where she teaches undergraduate courses in composition, literature, and publishing. She is currently completing her dissertation, and her research focuses on human-nonhuman relations and the ethics of representation in Victorian and postbellum American literature. She has published on coal-mine canaries and the risks of recognizing sentience in fin de siècle Britain. Catherine is committed to interdisciplinary modes of inquiry and practice, and she looks forward to establishing productive connections between literary studies and other disciplines, programs, and communities.

Catherine Burton is a doctoral candidate in English at Lehigh University, where she teaches undergraduate courses in composition, literature, and publishing. She is currently completing her dissertation, and her research focuses on human-nonhuman relations and the ethics of representation in Victorian and postbellum American literature. She has published on coal-mine canaries and the risks of recognizing sentience in fin de siècle Britain. Catherine is committed to interdisciplinary modes of inquiry and practice, and she looks forward to establishing productive connections between literary studies and other disciplines, programs, and communities.

Academia seems to foster a culture of complaint, perhaps because of the value placed on critique. Faculty and staff fall victim to this as well. This essay is a useful reminder of positive thinking. In my family we talk about being a Yea Sayer rather than a Nay Sayer. Those who advocate positive psychology stress looking at the positive.